The Lost Daughter (Kazakhstan)

Team

Author, director and performer Almira IsmailovaDuration: 1 h

Language: Russian

Subtitles: Estonian, English

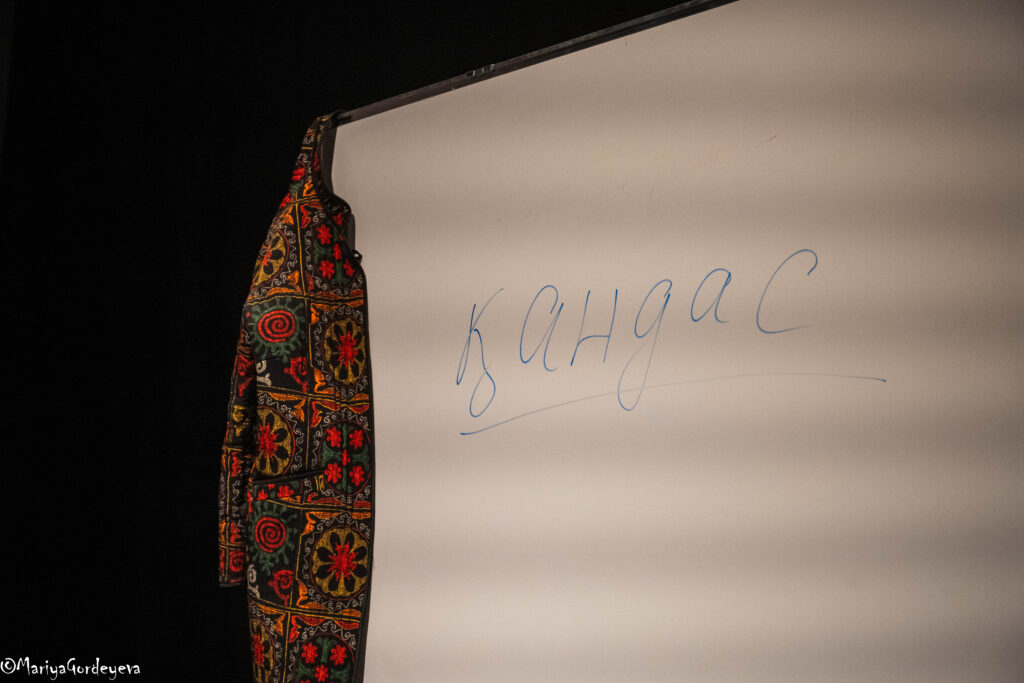

The performance “The Lost Daughter” explores the self-identification and social exclusion of repatriates, known in Kazakhstan as “kandas.” In the 1990s and 2000s, Kazakhs arrived mostly from Mongolia and China, perceived as outsiders, called “Mongols” or “Chinese”, and envied for the support they received. Only later did people begin to understand how difficult it was for them to integrate into society.

Based on both personal and academic research, the performance examines the connection between identity and language. Playwright and performer Almira Ismailova raises the question: What does it mean to be a Kazakh woman who does not speak her native language? The play and performance were created in collaboration with curator and director Elena Kovalskaya.

Learn more: Behind the Story of “The Lost Daughter”. Director and performer Almira Ismailova opens up.

1. Why did you choose this topic? How has it influenced your work and life?

I am a Kazakh woman, who grew up on the border with Russia and has always felt this pressure of the border. I absorbed Russian culture, as it was dominant. I don’t speak Kazakh, and this pains me a lot. I feel like it doesn’t give me the opportunity to get closer to my roots. That’s why I made a performance about identity. It became an important part of my inner decolonization. Talking to people after the performance, I realized how much people need a platform to discuss identity, the vulnerability of repatriates, and hushed-up political topics. I feel like I’ve found some kind of important break in society. The performance was invited to the Freedom Festival in Narva, and this is an important stage for my career as a playwright. And it is the proof that the topic resonates not only among Kazakhstanis. Well, the verbatim that I did with Kandases people improved my understanding of the Kazakh language.

2. Have there been any interesting situations during the rehearsals?

I can’t remember any interesting situations but it’s important to me that the performance took place in different locations. For example in the hotel room of Elena Kovalskaya – my mentor at Drama.Lab and the director of the performance. Also in the “shula” – it means something like a cubicle or warehouse in Uzbek, on the stage of Ilkhom, one of the first independent theaters in Central Asia. I played it at the recording studio and at the «Transform» theater in Almaty, at the American Space as a guest of the writer’s residence and rehearsed in the kitchen of my apartment. This is a project that fits into any space. I love it for its democratic nature.

3. Is there something else that the audience should know?

In the 1990s, after the collapse of the Soviet Union, Kazakhstan experienced a deep financial crisis. The population suffered greatly, and dissatisfaction with the authorities began to grow. Some of this frustration was unfairly directed at the Kandases (ethnic Kazakhs returning to their homeland) who were entitled to state benefits.

It’s important to understand that many of these Kandases had left Kazakhstan as a result of the forced sedentarization policies imposed on Kazakhs during the Soviet era. That rupture in their centuries old life caused deep generational trauma among those who left, those who stayed, and those who suddenly found themselves outside their ancestral homeland.

This context is essential to keep in mind when watching the performance. It speaks to the pain of displacement, the struggle for belonging, and the scars left by history.

Photos from the festival: Jelizaveta Gross